Cartoons Magazine * September 1915

Cartoons Magazine was published by H. H. Windsor through the Cartoons Publishing Company in Chicago. The magazine ran from 1912 to 1922 and featured political and social cartoons from a variety of cartoonists, many of whom were well-known for their work in major newspapers across the country. The magazine focused on using satire and humor to comment on current events, and it was especially popular during World War I for its commentary on politics and global affairs.

H. H. Windsor was also the founder of Popular Mechanics magazine, so he was deeply involved in the publishing world, particularly in magazines that combined entertainment with insight into society’s issues.

Cartoons Magazine and the Eastland Disaster

A somber look back at the September 1915 issue of Cartoons Magazine, focusing on the tragic Eastland Disaster in Chicago. This collection of century-old political cartoons and articles offers a poignant window into one of America's deadliest maritime disasters. The stark imagery and critical commentary reveal how artists and journalists of the time grappled with issues of public safety, corporate responsibility, and the human toll of the tragedy that claimed over 800 lives.

Source: Cartoons Magazine. Vol. 8, September 1915. Accessed September 20, 2024. HathiTrust Digital Library. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435069201069&seq=3&q1=eastland.

Cartoons Magazine cover, September 1915

Cartoons Magazine, September 1915 - Table of Contents

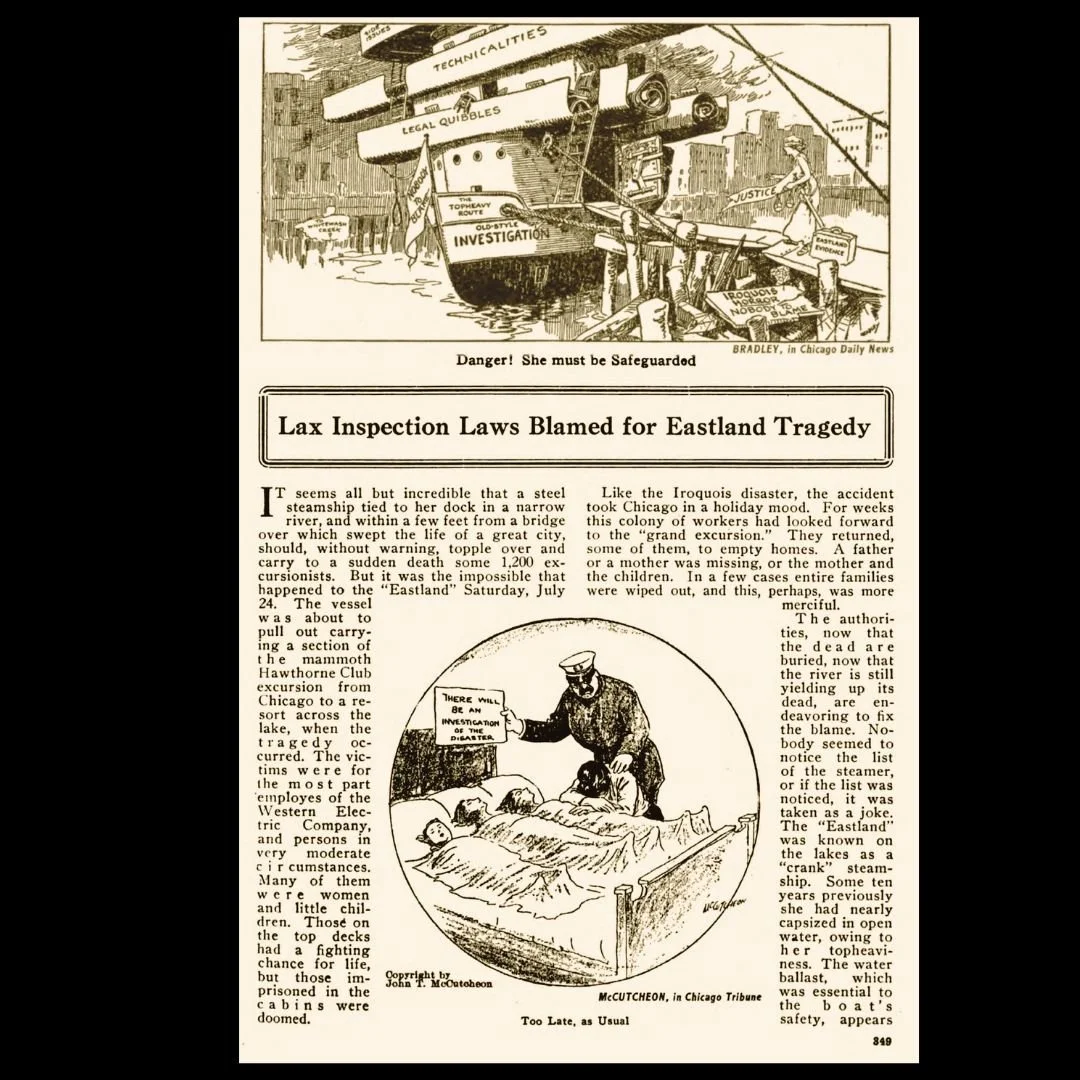

Lax Inspection Laws Blamed for Eastland Tragedy

The article places blame on lax inspection laws, poor regulations, and mechanical failures for the tragedy.

The top illustration is a political cartoon by Bradley, originally published in the Chicago Daily News. It depicts a ship named "Eastland" weighed down by "technicalities," "legal quibbles," and "posthumous investigation," symbolizing how bureaucracy and neglect led to the disaster. The message is clear: regulations should have been in place before the disaster occurred.

The Article:

The article emphasizes the shocking nature of the event, describing how the Eastland capsized in the Chicago River with no warning, killing over 1,200 people (the numbers are sometimes inaccurate in early reports, as mentioned in the article).

It compares the disaster to the Iroquois Theater Fire of 1903, another tragic event that claimed many lives due to insufficient safety regulations.

The article argues that many of the passengers, trapped in the cabins below deck, had no chance to escape, highlighting the failure of the authorities to ensure the vessel’s safety before allowing it to carry so many people.

The accompanying second cartoon, by McCutcheon of the Chicago Tribune, titled "Too Late, as Usual," shows an investigator standing over bodies, implying that the inquiry into the disaster came too late, after the lives were already lost.

Themes:

Negligence and Bureaucracy: Both cartoons and the article criticize how technical failures, legal loopholes, and delayed responses by authorities led to one of the greatest maritime disasters in U.S. history. The investigation, though necessary, only comes after the loss of life.

Public Outrage: The piece reflects the frustration of the public, calling for stronger safety measures and accountability.

Summary: This content serves as a reflection on the need for stricter inspection laws and highlights the devastating impact of ignoring safety warnings. It could be an important piece for your website to educate readers on the Eastland Disaster's historical context and the societal failures that contributed to the tragedy.

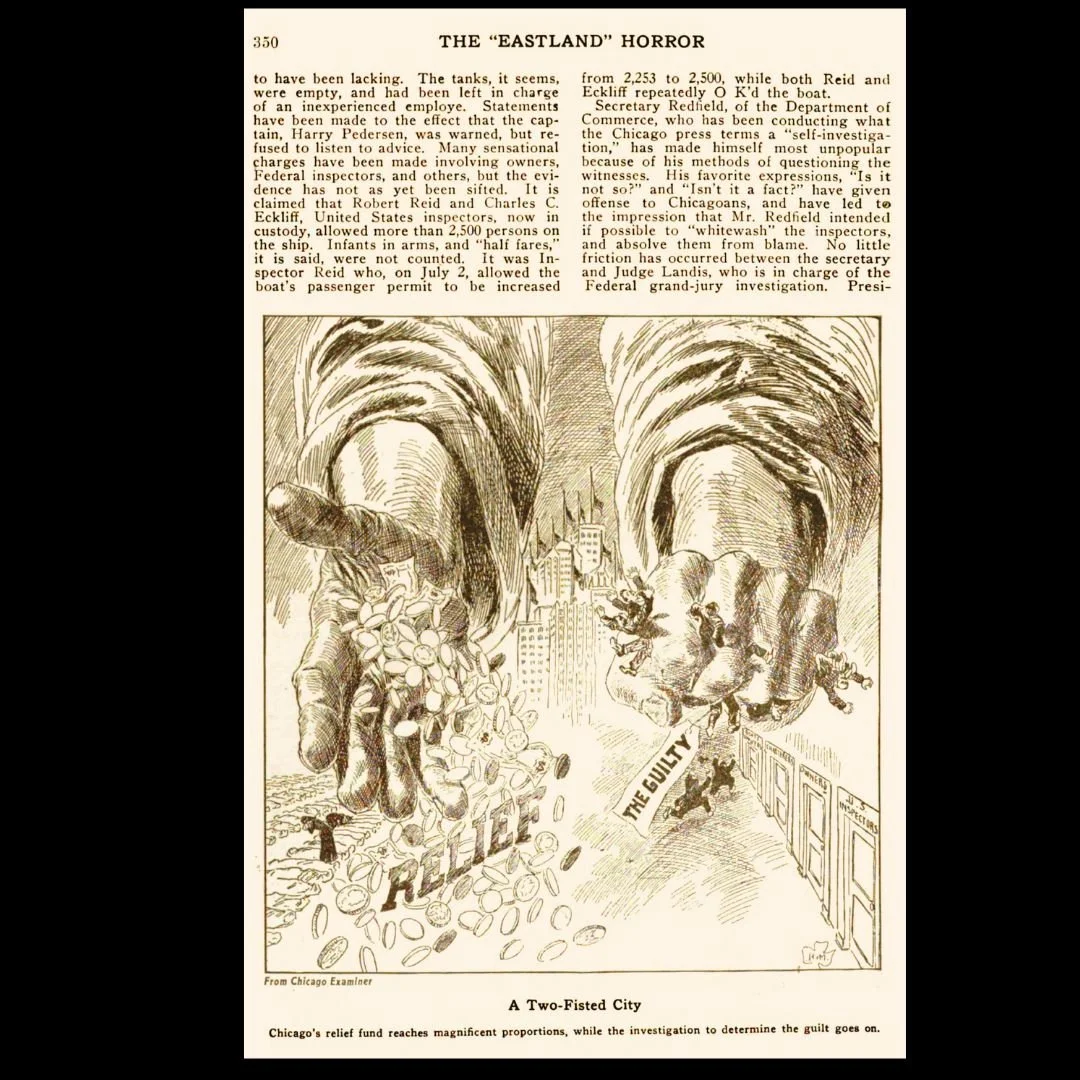

A Two-Fisted City

This page from Cartoons Magazine continues its coverage of the Eastland Disaster, diving into the investigation and the widespread blame placed on various officials for the tragedy.

The article details accusations against Captain Harry Pedersen and Federal Inspectors Robert Reid and Charles Eckliff, highlighting their roles in allowing the boat’s passenger capacity to be increased shortly before the disaster. Statements suggest that the captain had been warned about the ship’s instability but ignored the advice.

Federal inspectors are accused of negligence, and sensational charges are being made as the investigation continues. The controversy surrounding Secretary Redfield, from the Department of Commerce, suggests that he is conducting a self-investigation to shield the inspectors from blame.

The article mentions the manipulation of numbers, stating that infants and children were not counted in the final tally of passengers, adding to the confusion and outrage about the boat’s safety record.

The Cartoon:

The accompanying cartoon, titled “A Two-Fisted City,” illustrates Chicago responding to the disaster with both hands at work: one hand labeled “Relief” pours money to aid the victims and their families, while the other hand, labeled “The Guilty,” grasps at those responsible for the tragedy, representing the ongoing investigation and attempts to find accountability.

The cartoon underscores the dual efforts happening in the city—while money is being raised to support those affected, there is simultaneous pressure to hold the right people accountable for what happened.

Themes:

Negligence and Accountability: The article and cartoon both point to the growing frustration of the public with the slow-moving investigation and the seemingly evasive tactics of the officials involved. There is a clear call for justice to be served, but skepticism surrounds the actual progress.

Relief Efforts: While the investigation lingers, the community is stepping up to provide financial aid to those who lost family members in the disaster, showing the compassionate side of Chicago during this time of crisis.

Whose Safety First?

This page from *Cartoons Magazine* continues the discussion surrounding the aftermath of the **Eastland Disaster**, focusing on the investigation and public sentiment, while also highlighting the human side of the tragedy.

The piece emphasizes that President Wilson assured the citizens of Chicago that there would be no exoneration of those responsible for the disaster. Despite the ongoing war, the tragedy did not escape public and governmental concern.

A relief fund was quickly raised by Chicagoans for the survivors and the families of the victims, most of whom were left almost penniless. The article points to the case of a young boy whose body lay unclaimed at the morgue for several days before finally being identified. A patient at the Home for Incurables even offered his cemetery plot to the boy, symbolizing the compassion and unity of the city.

The article critiques Secretary Redfield's handling of the investigation, particularly his avoidance of responsibility and failure to accept the gravity of the Eastland’s safety flaws. The city, the article claims, does not seek punishment out of vindictiveness but rather wants justice and assurances that such a disaster will never happen again.

The Cartoon:

The accompanying cartoon, drawn by Bradley for the *Chicago Daily News*, portrays a businessman eager to fill the boat to capacity, ignoring safety concerns for the sake of money. The passengers appear fearful, with a man signaling for help as the ship appears ready to capsize. This illustration underscores the greed and neglect of safety that many believed caused the disaster, with profit being prioritized over human lives.

Whose Safety First?:

This section discusses how the Chicago Tribune editorialized the investigation, stating that Chicagoans were not interested in punishment for punishment’s sake. Instead, they were focused on ensuring safety regulations for excursion boats like the *Eastland* were reformed to prevent future tragedies.

The sentiment in Chicago was one of frustration and sadness, as people demanded not only justice but concrete steps to prevent such a loss of life from happening again.

Themes:

Negligence vs. Compassion: While the disaster was caused by greed and poor regulation, the response from the Chicago community was one of generosity and unity, as demonstrated by the relief fund and the heartwarming story of the boy's burial.

Public Demand for Justice: The article and cartoon convey the public's desire for accountability, safety reform, and reassurance that the victims’ deaths would lead to meaningful change.

This page would provide readers with insight into how Chicago dealt with the aftermath of the Eastland Disaster, both in terms of human compassion and calls for systemic reform. It highlights the tension between profit-driven neglect and the city's collective responsibility to care for its citizens.

“I never did feel safe on that boat”

This page from Cartoons Magazine continues its coverage of the Eastland Disaster, focusing on a heart-wrenching story of one of the youngest victims, as well as the broader societal implications of the tragedy.

This image includes a poignant editorial from the Chicago Daily News reflecting on the tragic death of a young boy, Willie Nowotny, who was initially unidentified after the Eastland disaster and known only as “the little fellow.” The article discusses the responsibility society has to care for children like Willie, highlighting their innocence and vulnerability in a world often too preoccupied with its own affairs. The accompanying cartoon, by Mr. May, features an elderly man named “Uncle Mose,” who comments, “I never did feel safe on that boat,” with an illustration of the Eastland capsizing in the distance.

Themes:

Innocence and Vulnerability: The article emphasizes the innocence of children like Willie Nowotny, who become symbolic of the helplessness and fragility of youth in the face of tragedy.

Neglect and Responsibility: It questions society’s neglect of its duty to protect “the little fellows,” highlighting a broader failure to care for the vulnerable, particularly children.

Human Compassion: The text reflects on the emotional impact of seeing an unidentified child victim, underscoring the universal need for compassion, care, and moral responsibility.

Mourning and Loss: The story of Willie Nowotny and his family being claimed from the morgue and laid to rest illustrates the personal grief families faced during the Eastland Disaster.

Critique of Society’s Priorities: It touches on how the fast-paced, practical world often overlooks the needs of the innocent in favor of focusing on more “important” adult concerns, stripping away their childhood innocence too quickly.

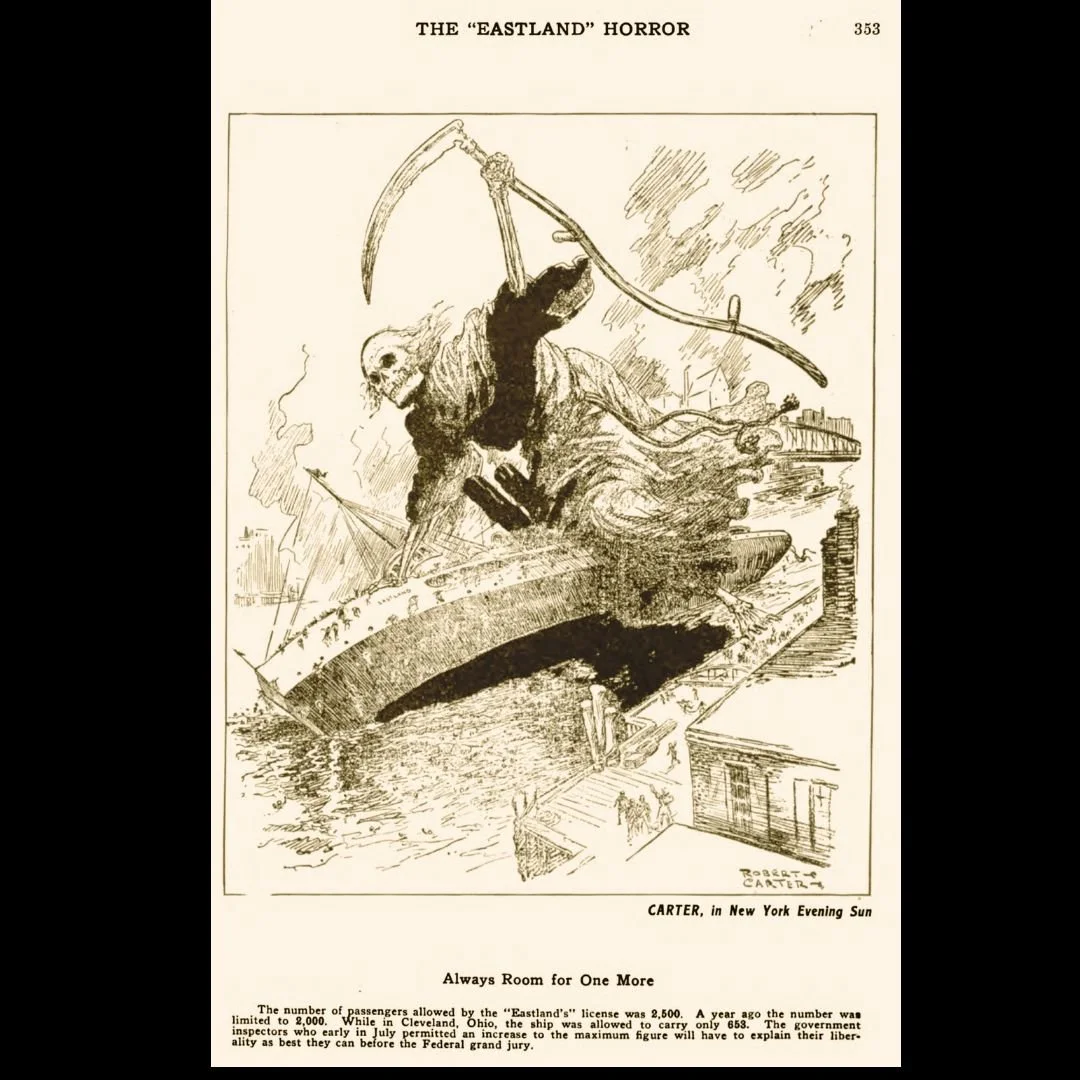

The Eastland Horror

“Always Room for One More” drawn by Robert Carter for the New York Evening Sun

This cartoon, drawn by Robert Carter for the New York Evening Sun, illustrates the Eastland disaster with a grim figure of death hovering over the capsizing ship, wielding a scythe, signifying the scale of the tragedy. The caption, “Always Room for One More”, is a dark commentary on the fact that the Eastland was allowed to carry more passengers than its initial capacity of 2,500, despite having been restricted to 2,000 just a year prior. On the day of the disaster, the ship was allowed to carry 2,500 passengers, even though inspectors previously reduced its maximum. The image and text highlight the negligence and poor decision-making by officials that contributed to the disaster’s high death toll, with those responsible facing scrutiny from a federal grand jury.